This article by Larry Wilson is reprinted with permission from the July 2001 Issue Occupational Health & Safety Magazine.

Ok… so it’s a catchy title. But, can you imagine hearing them down at the maternity ward: “Push, come on push… and one more… here it comes… and… now, one more big push… and… it’s a… it’s a… well—I’ll be darned— it’s a worker!”

Or, down at the police station: “Hey Fred, you were the lead investigator for that big pile-up on the freeway just outside of town—what happened?” “Well, what can I say—every single one of the cars involved was being driven by a worker…you know, they should pass a law so that workers aren’t allowed to drive.”

Of course, these scenarios are ludicrous. So is the idea of separating workers out as if they were a different animal (distinguishable at birth) or a different type of person (distinguishable through motor vehicle incident/injury statistics). Workers are people. People get hurt—everywhere— on a fairly regular basis. And we’ve been doing it all our lives.

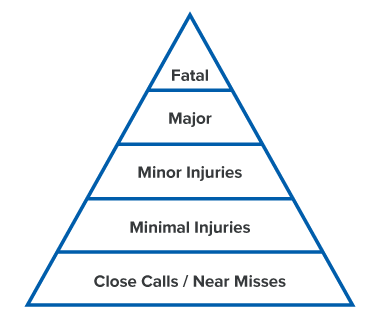

Young children get hurt 15 to 25 times per week. That’s 5,000 injuries you can barely remember. Many of them will be minimal. Unfortunately, some will be a little higher up on the old risk pyramid, where a kiss and a Band-Aid won’t be enough.

Older children, from age 5 to 12 don’t get hurt quite as often, maybe only 2 to 4 times per week. That’s still another 1,000 injuries or so. Then we go to high school. Then we go to work where, in some cases, we’ll be expected to work injury free. Perhaps the company or corporate office with this expectation is relying on what we learned in high school to keep us injury free. If so, they must have gone to a different high school than the rest of us.1

So, before high school is over, most people have already experienced 6,000–7,000 unintentional injuries. But it’s not over yet because after you’ve been doing something for a while, it’s easy enough to start getting complacent (just think about driving). So, while you’re not getting hurt quite as often as you did when you were a child or at high school, it’s not as if you’re going injury free. Maybe you’ve gotten yourself down to one injury per week or maybe even down to only one per month. But how many people do you know who never have a bruise or cut for a whole year?

And again, not all of these injuries will be minimal. Some will be minor (sprains, stitches, second degree burns, mild concussions, etc.), some will be major (fractures, dislocations, torn or severed ligaments, dismemberment, etc.) and some will be fatal. Some will happen on the road. Some will happen at home and, of course, some will happen at work. However, when people get hurt at work, it’s because of a “dumb worker”???

How did the whole “dumb worker” thing get started anyway? Perhaps it started out with “human error,” which then became synonymous with “worker error” which—since only dummies make mistakes, became “dumb worker.”

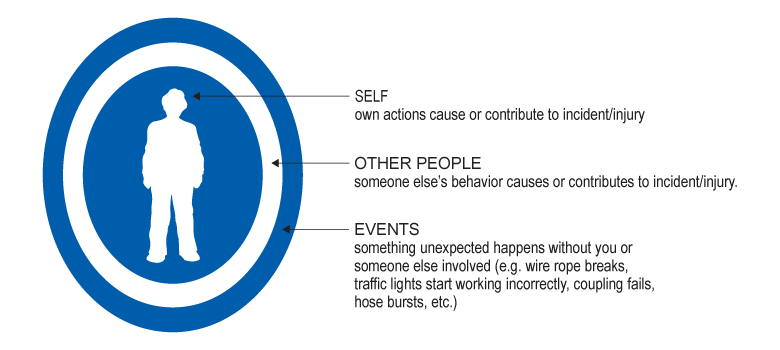

Now, it’s fairly well established that less than 10 percent of all injuries and incidents everywhere—at work, at home or on the highway—are caused by equipment failure or malfunction. What’s left, in terms of unexpected or unplanned occurrences, will be the people component. Most people are surprised that “the other guy” doing something unexpectedly—causing an injury—is also very low. During the last 16 years around 40,000 people in 300 different companies have been asked how many of their injuries were caused by the equipment or car doing something unexpectedly. The normal response has been about 2 to 5 percent. Then they were asked how many times the “other guy” doing something unexpectedly was a factor. The normal response has been about 5 to 15 percent—but for both of these questions, most people only had one example. What’s left is the “self area” (see Figure 2 below).

In other words, if it wasn’t the equipment or “the other guy” doing something unexpectedly to trigger the chain of events that lead to your injury—the unexpected source was you (or, in my case—me, in his case—him, etc.).

Did we intend to hurt ourselves? Not likely! So it must have been an error, miscalculation, misjudgment, etc. that triggered the chain of events. Or, as it might have originally started out—it was human error (our own) that triggered the chain of events. Not that this is new to any parent of small children. After all, when your child comes up the stairs crying—most parents ask, “Did you hurt yourself?”

Quite often you don’t even have to ask because the child is already volunteering it. “[Sob, sob]…I hurt myself…[wail, wail].” Sometimes, as mentioned before, a kiss or a Band- Aid will suffice—sometimes it won’t. Stitches or plaster might be needed.

But imagine asking a tradesman with 20 years’ experience coming into the first aid room, “Did you hurt yourself?” (Personally, I wouldn’t recommend it.) Yet how many times would the circumstances or the source of the unexpected really be all that much different from the child’s injury or the teenager’s injury or from those of another adult driving a car? How many times do you think you would hear: “I didn’t see it” or “I wasn’t thinking about it” or “I got hit by something” (being in or moving into the line-of-fire) or “I lost my balance, traction or grip”? These four errors (or a combination of them) are contributing factors in over 90 percent of all recordable injuries of an acute nature. If you go down a level on the pyramid to include bumps, bruises, scrapes and cuts, they are contributing factors in over 99% of all acute injuries.

Obviously then, if over 90% of all acute injuries are self-inflicted (caused by our own mistakes), reducing human error or minimizing its negative effects is the name of the game. Unfortunately, both of these strategies have not been given equal “air time.”

Advances in engineering controls, machine guarding, personal protective equipment and procedure design have had most of the limelight. And for good reason—these controls are very efficient. But can all hazards really be eliminated? Of course not! Yet there has been a reluctance, and in some cases a great reluctance, to look at reducing the unintentional mistakes we all make that can get us hurt. It’s much more popular to try to “fix” something. While “blaming” someone is useless (or worse), and doing nothing means you “accept” that the injury was not preventable—fixing something that didn’t contribute to the injury isn’t going to get you anywhere either.

Of all the examples that come to mind, the most extreme—in terms of fixing something that didn’t contribute to an injury—was of a hydro worker who was walking backwards in the parking lot telling a few of his co-workers a joke. He tripped on a concrete parking divider, fell down and broke a bone in his wrist. The utility company decided to paint all of the concrete parking dividers yellow. Even the most devoted union supporters recognized the ridiculousness. “What good would painting the dividers fluorescent pink have done? Unless the worker had eyes in the back of his head, he’s not going to see it, no matter what color it is…”

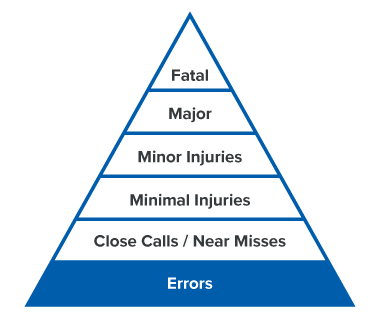

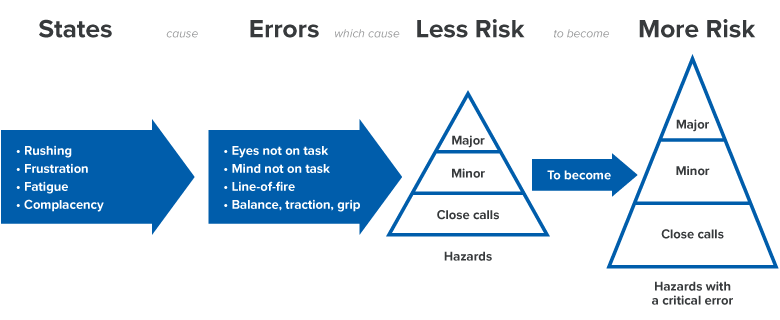

Can you minimize human error? Yes. The traditional behavior based safety approaches can reduce human error— but primarily through rote observation and repetition. It does work, even if it takes a fair bit of time and expense. However, an easier and faster way would be to simply look at what causes all types of error—and work on those human factors or states. In other words, go down even one level further on the pyramid and add error (see Figure 3).

What causes people to make mistakes? Well, lots of things. But if you asked those 40,000 people mentioned above, the number one cause you’d hear would be “rushing.” Not that this kind of news will knock your grandmother off her rocking chair. After all, “haste makes waste” isn’t exactly a new expression. Another cause or state you would hear—although not quite as often as rushing—would be fatigue. You’d also hear about frustration and complacency.

You might also hear about other states as well. But can you think of a time or of an injury that you’ve had that was in the “self area” ( not the equipment or “the other guy”) where you weren’t rushing, you weren’t frustrated, you weren’t overly tired or you hadn’t become so complacent with the hazards that you weren’t even thinking about the risk anymore? Now, can you think of a time or of an injury that you’ve had that was in the self area, where you were actually looking at what you were doing, thinking about what you were doing, aware of the line-of-fire and conscious of losing your balance, traction or grip? If you can, you’ll be the first in 40,000. In other words, one (or more) of these 4 states caused or contributed to one (or more) of these 4 errors. (See Figure 4).

Once you see these state to error patterns (and you see them everywhere), all you’ve got to do now is teach people to recognize when they’re in one of these states before they make a mistake, or a mistake that can get them hurt. Not only will this reduce injuries, it will also reduce quality problems, efficiency problems and needless equipment or vehicle damage.

While you’re teaching people how to make fewer mistakes, don’t slack off on your other efforts to minimize the negative effects if people do make mistakes—because they still will—(hopefully fewer after you’ve finished your training)—but they will still make some never-the-less. In other words, you need to do both. It may be imperative that you do not slack off in your efforts to make your workplace more “error tolerant” in order to avoid creating the impression that you’re throwing it all on the backs of the “workers.” Besides it’s far more efficient to eliminate or minimize the hazard itself whenever you can.

Again, the most extreme example of this that comes to mind was a graphics/ film company. They preferred to use tape dispensers with a heavy metal bottom so they could “one-hand” the tape to stick the film on the light tables. The serrated edge used to tear the tape broke off. What they did to fix the problem was to replace the serrated edge with a razor blade. Realizing that they put an additional source of danger (hazard) into the task, they put a warning sign on the tape dispenser (see Figure 5).

Everyone, including the owner and manager, sliced their finger or hand on the razor blade during the next few months following the “modification.” Apparently, the razor blade could not tell the difference between worker fingers and owner fingers—dumb fingers or intelligent fingers. Finally, after the owner had gone for stitches the second time, he contemplated hiring a safety consultant to come in and talk to the workers about improving their awareness, habits, behaviors, etc.

When he heard about it, the consultant said, “You’ve got to be kidding?” The owner said, “Well…we all know the razor is there—but every one of us has sliced our hand or finger….” The consultant told the owner to “just buy a new one—that way you don’t have to worry if people aren’t looking or they aren’t thinking for a second.” However, the consultant told the owner he would be happy to come in and talk to his employees about advanced awareness techniques because they drive on the QEW and 401– where you can’t just buy a new one. (Highway 401 in Toronto is the second busiest freeway in the world—16 lanes).

And the same advice would apply to everyone else. Minimize or eliminate whatever hazards you can. When you’ve come to the end of the line… then you can start looking at behavior. But, don’t back off or run away from human error because you think it might be construed as blaming the “dumb worker.” You can teach people how to make fewer mistakes and fewer injury-causing mistakes. Hundreds of companies have already done so and are enjoying significant reductions in recordable injuries. They’re also enjoying fewer off-the-job injuries and fewer motor vehicle related injuries and incidents. And morale didn’t go down. It went up. People aren’t stupid—they know how they’ve been hurt (it’s not as if we don’t have any data or experience—we’ve all been hurt thousands of times). When you give them something useful, that will actually help them on-the-job, off-thejob and especially while driving—they appreciate it. Some even take the concepts home to their families.

1 A total recordable injury rate (TRIR) of two means that 50% of the workforce will not have any recordable injuries in 25 years while the rest of the workforce will only have one recordable injury in 25 years (Two recordable injuries per 100 workers per year = two recordable injuries for one worker every 100 years, one recordable injury for one worker for 50 years or one recordable injury between two workers for 25 years).

Larry Wilson has been a behavior-based safety consultant for over 25 years. He has worked with over 2,500 companies in Canada, the United States, Mexico, South America, the Pacific Rim and Europe. He is also the author of SafeStart, an advanced safety awareness program currently being used by over 2,000,000 people in 50 countries worldwide.

Get the PDF version

You can download a printable PDF of the article using the button below.