By Rodd Wagner

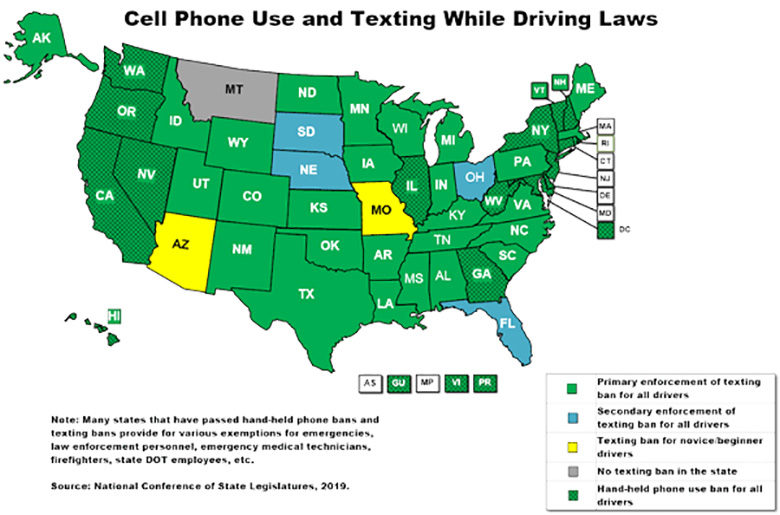

Last month, Minnesota became the latest state to outlaw handling a phone while driving. The law – which joins similar prohibitions in 16 other states and the District of Columbia – was too long in coming.

The new statute and those in the other jurisdictions are good laws in what they prohibit. But what they still allow, the evidence shows, is not good practice. Where these laws end, drivers’ better judgment will need to take over. Otherwise, the tragedies of distracted driving fatalities will continue to accumulate.

Hands-free laws prohibit manipulating a device that otherwise intelligent and responsible people seem to find irresistible. A smartphone’s alerts, vibrations, and lights hijack the distractibility that was a survival mechanism in our deepest ancestors and turn it into a deadly obliviousness.

When walking in the wilderness, turning to see the bear that made a twig snap could save your life. When driving 88 feet per second (60 miles per hour), reaching to see a new text or social media update could get you or someone else killed. Not only do the reflexive parts of our brains not know the difference between the twig and the text, the logical parts of our brains don’t appreciate our susceptibility to being cognitively yanked away from navigating the vehicle.

The phone tricks our brains into thinking we are paying attention.

Which we are.

To the phone.

For this reason, these laws are a long overdue step forward. But they are not enough. In fact, to the degree that people read it as an endorsement of hands-free cellphone use or hands-on console use, they could give a green light to forms of distracted driving nearly as dangerous as fiddling with the devices.

Most safety professionals are aware of the phenomenon of “inattentional blindness.” In traffic safety, it’s often labelled “Looked but failed to see.” In Great Britain, it goes by the acronym SMIDSY (“Sorry, Mate, I didn’t see you.”). The effect has been documented in eye-tracking studies. Even professional pilots have been documented to be looking directly at something and yet not have it register in their consciousnesses. On the road, it’s a human factor too powerful for all the “Start Seeing Motorcycles” bumper stickers to overcome.

One of the chief suspects in causing inattention blindness is the “cognitive workload” caused by multi-tasking. Brain imaging studies show that the amount of mental capacity dedicated to judging speeds and distances in making a left turn in traffic goes down substantially just from listening to the radio. The brain drain is more serious when trying to get Siri to understand you.

A 2017 study conducted by five University of Utah researchers tested drivers using Apple, Google, and Microsoft voice-controlled software to place a call, select music, or send text messages. While the drivers never touched the devices and were able to keep their eyes on the road, the cognitive “workload was significantly higher” than measured in what the researchers called “single-task” driving.

“Surprisingly high levels of cognitive workload were observed when drivers were interacting with the devices,” the researchers concluded. “The data suggest that caution is warranted in the use of smartphone voice-based technology in the vehicle because of the high levels of cognitive workload associated with these interactions.”

Minnesota’s new law specifically exempts “a device or feature that is permanently physically integrated into the vehicle.” Here, too, just because the law allows manipulating the increasingly common center consoles in newer vehicles does not mean one of them won’t get you killed just as certainly as texting on a smartphone.

Another 2017 study, also by University of Utah researchers, concluded that “in-vehicle information systems” or IVIS take attention from the road in much the same way as cellphones. “Our objective assessment suggests that many of these IVIS features are too distracting to be enabled while the vehicle is in motion,” they concluded. “This is troublesome because motorists may assume that features that are enabled when they are driving are safe and easy to use.” The new law’s exemption may reinforce that bad assumption.

The evidence could not be more striking. Those who don’t want to die or kill someone else on the road need to not only avoid touching their phones while driving, but generally avoid trying to talk to them while driving. It takes little time to set up the devices with whatever podcast or navigation is wanted for the drive and not interact with them – hands-free or otherwise – until safely parked again. Otherwise, these seductive devices will continue to be the killer app.

Rodd Wagner is a New York Times bestselling author, Forbes contributor, and executive advisor at SafeStart. He is currently completing work on a book about avoiding the mental mistakes that cause fatal accidents.