This article by Andrew Faulkner was published in the

summer 2015 issue of The Leader

Kyla Cullain received a Bachelor of Science in Nursing in 2008 and quickly found a job with a municipal public health unit. As part of her schooling she received instruction on proper body mechanics but there were no practice situations that simulated working conditions. Once she joined the workforce there was the expectation that the safety skills she learned while training to be a nurse were more than sufficient.

You’re reading this in a safety magazine so you probably already know that it wasn’t enough.

There was a long stretch of days when Kyla’s team was tasked with urgently providing vaccines to group homes. The schedule was demanding and at each home they were forced to set up makeshift clinics in whatever office space they could find. As she was packing up at one location so that she could rush off to the next, she bent over to retrieve her cooler of vaccines from a cramped corner.

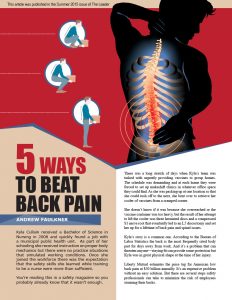

She doesn’t know if it was because she overreached or the vaccine container was too heavy, but the result of her attempt to lift the cooler was three herniated discs and a compressed S1 nerve root that eventually led to an L5 discectomy and set her up for a lifetime of back pain and spinal issues.

Kyla’s story is a common one. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics the back is the most frequently cited body part for days away from work. And it’s a problem that can threaten anyone—staying fit can provide some protection but Kyla was in great physical shape at the time of her injury.

Liberty Mutual estimates the price tag for American low back pain at $50 billion annually. It’s an expensive problem without an easy solution. But there are several steps safety professionals can take to minimize the risk of employees straining their backs.

1. Follow the hierarchy of controls

The hierarchy of controls should be your first step in minimizing back strain among workers. This includes obvious steps like minimizing lifting where possible, eliminating any twisting required when lifting, and reducing the frequency and distance that employees have to bend over or lift above their head.

But in most cases, it’s impossible to completely eliminate the hazard and engineering solutions are limited—lifting is an unavoidable element of many jobs and weight is a function of gravity. And when it comes to PPE, there’s a single fact that gets ignored in far too many workplaces: back belts don’t work.

Frequent back belt use wasn’t effective at reducing back injury claim rates or self-reported back pain.

– from a study in the Journal for Occupational Rehabilitation 2012

A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association examined over 13,000 material-handling employees at 160 retail stores across the United States to determine the effectiveness of back belts and policies requiring their use. After observing these employees for two years and adjusting for multiple risk factors, the study concluded that frequent back belt use wasn’t effective at reducing back injury claim rates or self-reported back pain.

Not only have back belts been demonstrated ineffective, but in some cases they may actually have a negative effect. They could give employees the mistaken belief that they can attempt to lift more than is safe or lend employers a false sense that their workers’ backs are adequately taken care of. Better to provide proven devices that directly help with lifting.

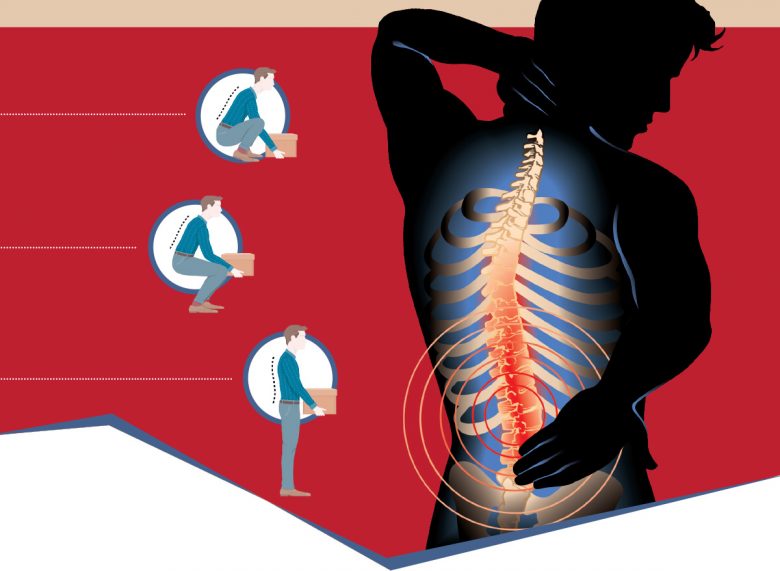

2. Teach—and practice—safe lifting techniques

Too many back training programs consist of gathering employees in a room once a year, showing a 10-minute DVD with outdated footage and then sending them back to work once it’s over. The lifting techniques in these videos may be perfectly applicable because there hasn’t been any major breakthroughs in lifting procedures for years, but information transfer is only one part of safety training. It’s also essential to provide frequent, hands-on training to increase the likelihood that workers will retain the knowledge.

It’s important to remember that back safety training almost always happens in a controlled environment without the stress and hustle of the workplace. If you want employees to remember safe lifting procedures when they’re rushing, frustrated or tired they need to practice lifting demos and receive regular positive correction and feedback. Ideally, they should also be trained in identifying and contending with the human factors that are most likely to compromise their lifting technique.

It’s important to remember that back safety training almost always happens in a controlled environment without the stress and hustle of the workplace. If you want employees to remember safe lifting procedures when they’re rushing, frustrated or tired they need to practice lifting demos and receive regular positive correction and feedback. Ideally, they should also be trained in identifying and contending with the human factors that are most likely to compromise their lifting technique.

Frequent reminders are also important. In a 2014 survey of safety professionals conducted by BLR, 85% of respondents said that reminding workers about safety issues is effective but only provides a temporary benefit. The survey focused on slips, trips and falls in the workplace but many of its findings, including this one, are broadly applicable to safety practices. This means that not only should you provide reminders but you also need to offer training that will keep workers safe in between their reminders—including building better habits.

3. Build better habits

The Society for Personality and Social Psychology notes that 40% of our daily behavior is habitual, echoing a longstanding belief that a great deal of our behavior is a result of routines. Many people have established lifting habits long before they enter the workforce, and these habits play a huge role in determining the long-term status of an individual’s back health.

Back injuries can result from a single incident, but they can also be caused by a history of poor lifting techniques that compound over time. A paper published in the Journal for Occupational Rehabilitation in 2012 discovered that cumulative load on the lower back is more consistently associated with lower back pain than previously identified risk factors. Improper body position can also be a contributor, and overreaching or excessive torque can make lifting even small weights have a big impact on your back. And whether it’s one lift or a thousand lifts, once the total load you’ve carried exceeds your limit you’re at risk of an injury.

Back injuries can result from a single incident, but they can also be caused by a history of poor lifting techniques that compound over time. A paper published in the Journal for Occupational Rehabilitation in 2012 discovered that cumulative load on the lower back is more consistently associated with lower back pain than previously identified risk factors. Improper body position can also be a contributor, and overreaching or excessive torque can make lifting even small weights have a big impact on your back. And whether it’s one lift or a thousand lifts, once the total load you’ve carried exceeds your limit you’re at risk of an injury.

In Kyla’s case, the strain of lifting the container of vaccines led to an injury but it didn’t occur in isolation. Rather, it was the culmination of years of bad body mechanics catching up with her. “Hauling out the vaccine cooler was a trigger but it definitely wasn’t the only factor in my injury,” she notes. “Looking back, I definitely had something coming and it was just a question of what would set it off.”

Your training program should identify important backhealth habits, like reaching your arm out to build a bridge when bending over, and should provide employees with the support they require to properly form habits that will protect their back throughout their career.

If you want employees to remember safe lifting procedures when they’re rushing, frustrated or tired, they need to practice lifting demos and receive regular positive correction and feedback.

4. Identify the workplace risks

Knowledge is power and there’s no better way to avoid unsafe lifting techniques than to make sure employees know their safe lifting thresholds and which oddly shaped objects are most likely to cause them to alter their approach to lifting.

Teach employees to recognize awkward or dangerously large loads and help them learn to quickly spot instances when they should ask for help. “The thought never crossed my mind that the cooler was too big for me to carry or that having to reach out and bend for it would make it trickier to move,” Kyla says. “It also never occurred to me that I should ask for help.” Among the measures she thinks could have helped her prevent her back injury, hazard identification and awareness is at the top of the list. So too is avoiding rushing through a task without taking the time to ensure she’s employing the proper techniques.

Not all hazards come in big packages. In some cases, the danger may be repetitive strain rather than large loads. In these cases, provide ample breaks for rest and recovery, and consider periodically rotating employees to other positions that demand less from their backs.

5. Appeal to their agenda

Everyone has a safety agenda. Employers typically aim to minimize workplace injuries to keep their workforce healthy, productive, and to avoid potentially costly workers’ compensation expenses. Unsurprisingly, employees have a more personal take on the issue—they want to stay healthy so they can provide for their family, coach their kid’s softball game after work and continue enjoying all that life has to offer.

The goal is the same but the motivations are much different. You’ll get much better employee engagement when you appeal to the employee’s personal agenda rather than a corporate mandate.

The goal is the same but the motivations are much different. You’ll get much better employee engagement when you appeal to the employee’s personal agenda rather than a corporate mandate.

This can take a number of different forms, from creating training collateral that provides off-the-job examples to frequent reminders that a back injury will affect their entire life, no matter where it occurs. Addressing off-the-job safety is a surprising but effective solution to workplace back injuries. Employees who are aware of the off-the-job cost of straining their back and who practice safe techniques at home are more likely to stay safe at work too.

Back injury prevention revolves around employee behavior and buy-in. You can’t force anyone to follow safe lifting practices so you need to educate them on its importance, give them the skill set to reliably perform safe behavior on the job, and recognize when their approach may be compromised by human factors. Because once a back injury occurs, there’s little you can do but accommodate the employee as best you can.

Kyla is now the CEO of Next Step Transitions Inc., a company that provides barrier-free living and safety aids to seniors, and she understands the importance of prevention and risk awareness. When asked if knowing her safe lifting limit and the dangers of rushing would have changed things, she answers quickly, “There’s no doubt in my mind that more training and recognizing the real risks of rushing could have helped me avoid getting hurt. If I’d taken the time to better assess the situation things would have been completely different.”

Get the PDF version

You can download a printable PDF of the article using the button below.