This article by Larry Wilson is reprinted with permission from the

June 2000 Issue Occupational Health & Safety Magazine.

Employees need a motivational component and an environment that gives them the opportunity to think about their own experiences on and off the job.

Thousands of companies worldwide have successfully implemented a behavior based safety process, but it hasn’t always been smooth sailing. Specifically, behavior based safety has three main drawbacks: the time it takes to see significant results; the expense required to get it off the ground; and the potential conflict that may arise from observing at-risk behaviors that are also covered under rules and regulations. Unless these obstacles can be minimized or eliminated, behavior based safety—despite the overwhelming attention it has received in the last decade—is not likely to become the mainstream vehicle for reducing accidental injuries in the workplace.

Why have these companies bothered with behavior based safety at all? Because for the ones that implemented it properly and stayed the course at least three to five years, the results have been amazing. Incidents and injuries decreased, and morale went up. It is not uncommon for a company to see a 30 to 50 percent reduction in injury rates in the first two years, and 50 to 90 percent over a five-year period.

Moreover, the safety culture changed, and participation and involvement improved. By the third or fourth year, employees would tend to develop an increased sense of awareness for critical behaviors off-the-job and while driving.

Who wouldn’t want world-class incident rates, a positive safety culture, good morale, high levels of involvement and participation, and better off-the-job safety performance?

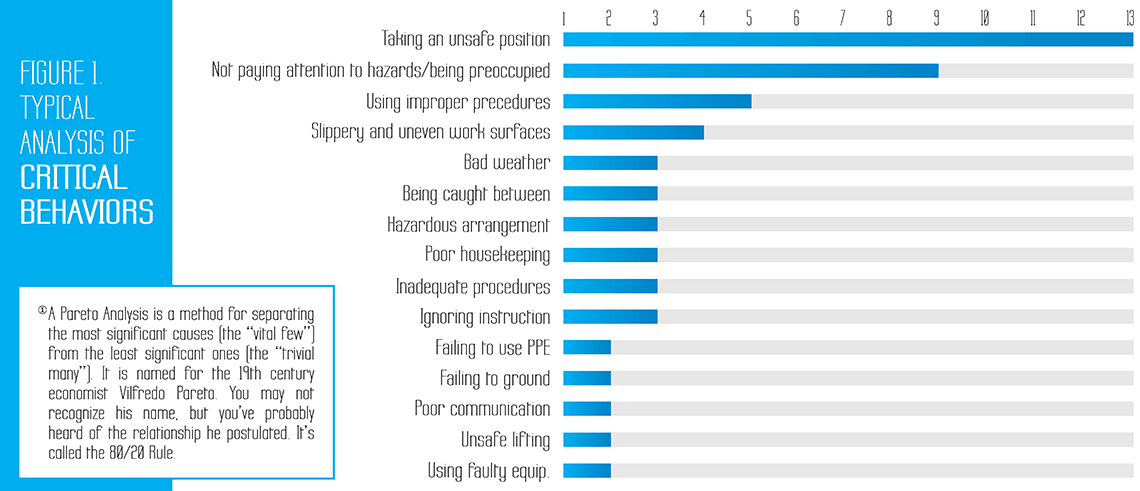

The behavior based safety process is not rocket science. It starts with a Pareto Analysis of about five years of incident investigation data to determine behaviors (or factors) that contributed to 85 to 95 percent of injuries. For most companies, there are about 10 to 20 of these “critical behaviors” (see Figure 1).

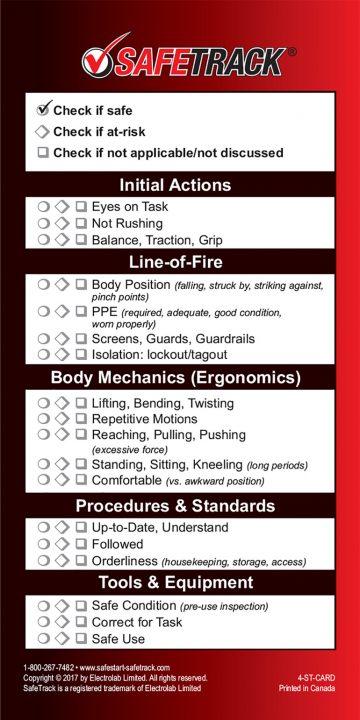

Observers are then trained on how to constructive feedback, which if done properly will improve the likelihood that these critical behaviors are performed safely. The observations are recorded, and the percentage of the observations that are safe is tracked. As the “percent safe” increases, injuries tend to come down—dramatically, in some cases.

Why success takes time—and money

Behavior based safety takes time. It requires at least a three-year commitment, and not everyone has the patience to stay the course long enough to see results. One of the reasons behavior based safety takes so long is because there are comparatively few people actually involved in the change process, other than during the observations.

Competent observers who are skilled at giving appropriate feedback are critical to its success. Through rote observation and repetition, critical behaviors are eventually brought up to “habit strength,” which means that even if the employee isn’t thinking about the risk, the behavior will be performed safely. Getting behaviors to habit strength through repetition takes time.

A typical behavior based safety implementation has around 10 to 15 percent of the workforce trained to be observers. In most cases, the observer will make about one or two observations a week. That means an average employee can expect to be observed about once every four to six weeks. The observations take around five to 10 minutes. Five to 10 minutes per month is not enough to make a decisive difference in behavior in a short period of time.

The second drawback of the traditional behavior based safety process is the money required to get the process off the ground. Consultants cost money, and good consults cost a lot of money. Consultants are often used because they’ve been through the process scores of times before. They know the mistakes you’ll be tempted to make. They know how to turn the naysayers into cheerleaders. They know how to keep the focus on the things that matter. Yet, some people might argue this money would be better spent fixing unsafe conditions or improving the ergonomics of certain workstations. Depending on what has or hasn’t been done, this question might have a great deal of validity.

Finally, there is the potential conflict that can result if rule violations are observed and discipline is brought into the process. Even though everyone who works in the behavior based safety field advocates that discipline should not be brought into the process on actual observations, many employees fear behavior based safety will just become an extension of the current progressive discipline structure. Very few people will be interested in making observations if they are worried that what they observe will get someone in trouble. These apprehensions are actually part of the reason it takes a good consultant to get the process off the ground. The aforementioned expense associated with good consultants brings you back to the second drawback: “Why aren’t we spending this money elsewhere?”

You could choose to ignore the behavioral aspect of safety and pretend that it does not exist. But that would be to ignore the obvious. Just think about driving your car.

It is estimated that more than 90 percent of vehicle collisions or car wrecks are caused not by weather conditions, road conditions, or mechanical integrity of the car—but by drivers and driver error. The term “driver error” should not imply that it’s the drivers’ fault and that they are to blame. After all, who wants to end up in the hospital as a result of not seeing a red light? Instead, “driver error” should refer to unintentional mistakes and poor habits. If you re-engineer all the dangerous intersections without at the same time getting through to each driver what it means to drive defensively, your program to reduce injuries and fatalities on the highway won’t be nearly as successful as it could be.

The workplace may look different because it’s easier to control the hazards. But just like the highway, all the hazards can’t be controlled all the time. If you tried to eliminate all unsafe conditions without at the same time getting through to workers that they play a crucial role in their own safety; again, your program to reduce incidents and injuries in the workplace won’t be nearly as successful.

People won’t make observations if they worry that what they observe will get someone in trouble. Their apprehensions are one reason it takes a good consultant to get the process off the ground.

Getting better results

But can the drawbacks of the traditional behavior based safety process be minimized or eliminated so that every workplace can enjoy the benefits—especially the increased sense of awareness for critical behaviors? Yes! Integrating new ideas and techniques with the traditional behavior based safety process can minimize or eliminate the drawbacks. Here’s an overview of the specific steps that can be taken:

1. Conduct a Pareto Analysis of your existing critical behaviors. What you’ll find is that a core group of critical behaviors—or critical errors, if they aren’t performed safely—will be on your checklist, no matter what type of industry your company is in. These are:

- Eyes not on task

- Mind not on task

- (Moving into or being in) the line-of-fire, and

- Somehow losing your balance, traction or grip.

What is interesting and important in the political sense is that these are, for the most part, unintentional at-risk behaviors that do not fall under rules and regulations or discipline-type issues. Changing the consequence structure can change behaviors that are deliberate. But how do you teach people to make fewer mistakes or errors, the ones they were never trying to make in the first place? Something new is needed, unless you want to wait for the rote observation/repetition method to work.

2. Recognize that before an error occurs, there is almost always at least one state (human factor) that predicates the error. If you talk to workers who have never been seriously hurt in more than 20 years even though they work at very high-risk workplaces (companies with a total recordable injury frequency over 100 percent), you’ll get some pretty good advice. When asked what was the most important thing they figured out in order to keep from being hurt, the most common response was, “Don’t rush.” Others said, “Make sure you get some sleep and don’t work if you’re really frustrated or upset.” Although they did not express it in terms of “complacency,” others were doing things to actively fight complacency. In other words, they were concerned that one of these states:

- Rushing

- Frustation

- Fatigue

- Complacency

…could actually cause them to make a critical error.

If you aren’t looking at what you’re doing and you’re not thinking about what you’re doing, all the specific hazard training in the world won’t do you any good at that moment.

3. Train all employees right from the start about the “state to error pattern.” Explaining the behavior based safety process is important. They need to understand that they need to be actively involved in the process whether they are being observed or not. They also need to understand that behavior based safety isn’t just something you do at work. It applies whether you’re on the job, off the job, or just driving your car.

How do you get this information across at a deep enough level for it to do employees any good? The training that’s required is much more than simply passing information along. To tell employees to “watch what you’re doing and think about what you’re doing and you won’t likely get hurt” is true, but it won’t actually help them very much. There must also be a motivational component that allows employees to decide for themselves. They need an environment that gives them the opportunity to think about their own experiences on the job, off the job, or driving.

They need to ask themselves if they have ever experienced a serious injury without one or more of these four states contributing to one or more of these errors. Very, very few people can relate a personal example of injuries that fall outside these patterns. (Can you?)

4. Give employees specific techniques they can use to minimize the risk of making a critical error. Show them how to trigger on each of the states and use them as personal activators to avoid making a critical error that increases the risk of contacting hazardous energy. Explain the value of watching or observing other people for these “state to error patterns” so they can fight complacency and become more aware of their own personal safety. Help them analyze their close calls such as small bumps and bangs (eyes not on task), so they won’t have to analyze the big ones.

This will make them more aware of the state they were in or any habit (such as turning your body before moving your eyes) that contributed to the error. Finally, demonstrate the importance of working on physical habits (such as testing your footing before committing your full weight when getting out of your car), to eventually developing the mental habit of thinking about and looking for line-of-fire and things that could cause you to lose your balance, traction, or grip.

To tell employees to “watch what you’re doing and think about what you’re doing and you won’t likely get hurt” is true, but it won’t actually help them very much. There must also be a motivational component that allows employees to decide for themselves.

Using follow-up observations

Training all employees up front about the “state to error pattern” and the techniques they can use to minimize the risk of making a critical error make the behavior based safety process more efficient. Teaching workers, in enough depth, how to get better at looking for and habitually thinking about line-of-fire and what could cause them to lose their balance, traction, or grip increases the efficacy of the rest of your company’s safety training. Because if you aren’t looking at what you’re doing and you’re not thinking about what you’re doing, all the specific hazard training in the world won’t do you any good at that moment.

Following up this training with regular observations takes the observations to a much higher level. Critical behaviors are brought up to habit strength much quicker because workers have the tools to get their hands around their own critical behaviors first. It also eliminates the need for a lot of front end loading to get the workforce to endorse and participate in behavior based safety. Because you can eliminate most of the consulting required to get the process off the ground, the expense is more reasonable.

There are some incredible benefits to behavior based safety and there are some significant drawbacks. By following the steps outlined above, the drawbacks can be minimized and the benefits maximized. Industries traditionally opposed to behavior based safety, such as railroads and assembly plants, already are seeing great results. These new ideas and techniques will allow more and more companies to use behavior based safety to improve their safety performance—both on and off the job.

Larry Wilson has been a behavior based safety consultant for over 25 years. He has worked with over 2,500 companies in Canada, the United States, Mexico, South America, the Pacific Rim and Europe. He is also the author of SafeStart, an advanced safety awareness program currently being used by over 2,000,000 people in 50 countries worldwide.

Get the PDF version

You can download a printable PDF of the article using the button below.