This article by Larry Wilson appeared in the September 2010 issue of Occupational Health & Safety Magazine, and is based on the presentation at the National ASSE and VPPPA conferences in San Antonio, Texas.

Driving home from the rec. centre last week, I saw a familiar scene starting to build on the side road next to the highway.

It was the usual suspects: an ambulance, more than one police car, a fire truck, another on the way—sirens blaring, the street being closed off…

In a few blocks, I was home. The neighbours were asking if I knew what happened.

“No, I don’t,” I said. “But whatever it was, it didn’t look good—too many police cars and fire trucks for something minor.”

“Was it on the highway?”

“Are they going to close the highway down?”

I answered both people at once. “No— it was on the Mons side road. They’re closing it down. Or, at least it looked like they were going to close it down.”

My seven and nine year old girls were on their bikes. They asked if they could ride over and see what was going on. I said I didn’t think that was a good idea. Whatever happened—one thing I was sure of—it wasn’t going to be pretty.

Several hours later, we eventually heard what happened: a flatbed transport truck (18-wheeler) hit a man on a mountain bike crossing the road—in broad daylight. The truck wasn’t speeding.

“How can you get hit by a transport?” one of my friends asked.

“Must not have seen it,” I offered.

“Yeah, I know, but that’s what I mean—how can you not see a transport truck?”

“Not easy,” I said in agreement. But in my head I’m thinking complacency. You’ve got to be pretty complacent to not see a transport truck. He must not have even looked. Heck, just a quick glance probably would have been enough. If he had just slowed down enough to get that quick look, he’d still be alive…

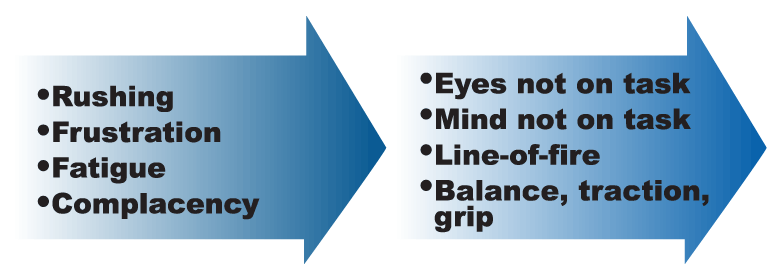

With violent crime, quite often you hear yelling and screaming before the gun shots. In the movies, the music changes, but with complacency there’s usually no warning, nobody’s worried about anything, and then “wham”— somebody’s dead—every day, thousands (and thousands) of times a day, all over the world. When you add it all up, complacency contributes to more unintentional deaths than anything else—especially when you combine it with rushing, frustration or fatigue.

How do people get so complacent that they don’t look for transport trucks or that they fall asleep at the wheel? Why do people get so complacent that they don’t even think about the risk anymore? (When was the last time you “worried” about your safety as you got behind the wheel?) How do people get complacent enough that they will do something that they know contributes to making a “mind not on task” error, like texting while driving? Or to not use a safety device like a fall arrest harness that reduces the risk if they do happen to make an error with balance, traction or grip? And finally, since it happens to all of us—we all do get complacent—what can we do to fight it?

Complacency and “Mind Not on Task”

As mentioned above, complacency causes many problems, but the biggest or the worst is that it leads to “mind not on task.” Once the fear is no longer pre-occupying, your mind can wander. And when you’re thinking about something else, other than what you’re doing at the moment, your most important asset—your star player—is sitting on the bench. Think about all of the times you’ve been hurt (not including sports). Can you even think of one time in your life when you’ve been hurt when you were thinking about what you were doing and the risk of what you were doing at the exact instant when you got hurt? Note: If you’re like most people, you can’t even think of one—let alone ten. And yet we’ve all been hurt thousands of times if you count all of the cuts, burns, bruises and scrapes we’ve had.

Case in point: I asked the question to over 1,200 linemen of a major electrical utility. Out of 1,200 lifetimes—on and off the job—I got two examples. The average age of the group was about 45. That’s two examples in 1,200 x 45 years.

Your mind is indeed your most important safety device

So, as mentioned before, your mind is indeed your most important safety “device”. But here’s the catch: we don’t always need to be thinking about what we’re doing—from a risk perspective—in order to do many things (like drive) without getting hurt. We can all do lots of things on auto-pilot. So the first thing people need to do is recognize or accept that their mind will wander if they’ve done the same thing many times before. It’s going to happen. It happens to everybody. It doesn’t make you a bad person—just a dead one, or a disabled one or a lucky one… But it’s not hopeless. There are techniques you can use to fight complacency, and there are techniques you can use to compensate for complacency leading to mind not on task—and mind not on task leading to line-of-fire or balance, traction or grip errors. They don’t require expensive equipment or yellow and black hashmarks. But they do take a bit of personal effort. And finally, besides teaching people these techniques, we also have to teach them to develop a deep level of respect for complacency and what it can do so that it doesn’t start creeping in to their decision making as well.

Critical Error Reduction Techniques

Although everyone does get complacent with things they have done over and over, it’s not hopeless, because if you’re not thinking about what you’re doing, your behavior will be what it normally is.

Although everyone does get complacent with things they have done over and over, it’s not hopeless, because if you’re not thinking about what you’re doing, your behavior will be what it normally is.

And it will only change if you make a conscious effort to change it. So we need to get people (including ourselves) to work on their safetyrelated habits: like moving your eyes before you move your hands, feet, body or car; testing your footing or grip before you commit your weight to it; looking at your “second foot” as you step over a cord or something that you could trip on (it’s usually the second foot—that you’re not paying attention to—that gets caught or hung up); looking twice when the sun is in your eyes to make sure you didn’t miss something (the sun does play tricks on you); lightly touching something before you grab it—if it might be hot (I learned this one at a steel mill); and finally—sadly in the case of the mountain biker—habitually looking for line-of-fire or what might be coming at you at blind intersections (or where bike trails through the woods exit onto a side road). Because, if you don’t see what might be coming at you, it could easily be the last mistake you’ll ever make…

Of course it takes a bit of effort to develop new habits or to change old ones, but the real bonus is that once you do—you will do it automatically. It won’t take any effort after that. And then you won’t have to worry nearly as much about complacency leading to mind not on task and mind not on task leading to other critical errors like lineof- fire and a loss of balance, traction or grip. However, even though improving your safety-related habits will help to compensate for your mind going off task, it would also be good if we had a way of helping people “pull their mind back into the ballgame” or to bring them back to the moment. This is because your habits and reflexes alone don’t give you the ability to anticipate a dangerous situation and then take yourself completely out of harm’s way. That you need your mind for.

However, if you watch other people for “state to error” risk patterns (see Fig. #1), every time you see one, it will automatically make you think more about what you’re doing. And, if what you see is sensational enough, you’ll do more than think about it— you’ll actually react to it. For instance, instead of just driving on auto-pilot you look around a bit more. As you do, you notice the driver beside you trying folder while talking to someone on the phone…

Chances are you’re going to either speed up or slow down or move over another lane to get out of the way.

But if you didn’t look or you don’t get in the habit of looking, then you wouldn’t necessarily take yourself out of the line-of-fire.

So, working on your safety-related habits helps to compensate for complacency leading to mind not on task, and looking at others for state to error risk patterns helps to pull your mind back into the ballgame and make you think about the risk of what you’re doing at the moment.

Complacency and Decision Making

While these two critical error reduction techniques will reduce injury causing errors like eyes not on task, moving into the line-of-fire and losing your balance, traction or grip, we also need to help people realize the problems complacency can cause with decision making.

One of these problems is with trusting something important—especially something that is important or critical from a safety perspective—to your memory. This can be as simple as forgetting to bring a lifejacket for everyone in the boat, to something more complicated, like remembering a change to a well-established routine (driving to and from work). In some cases, the consequences are just wasted time or wasted money. In others, if there’s enough hazardous energy around, the consequences can be deadly. (Approximately 100 children/infants a year die in Canada and the United States of hyperthermia because they fell asleep in their car seat and their parents forgot they were in the vehicle.)

One of these problems is with trusting something important—especially something that is important or critical from a safety perspective—to your memory. This can be as simple as forgetting to bring a lifejacket for everyone in the boat, to something more complicated, like remembering a change to a well-established routine (driving to and from work). In some cases, the consequences are just wasted time or wasted money. In others, if there’s enough hazardous energy around, the consequences can be deadly. (Approximately 100 children/infants a year die in Canada and the United States of hyperthermia because they fell asleep in their car seat and their parents forgot they were in the vehicle.)

So, when you say to yourself, “I’ve got to remember this,” or “I can’t forget to do that”, you need to realize that “right now” is your last clear chance to do something to aid your memory (note in line of vision, alarm on PDA/Blackberry, etc.). But once again, complacency can get in the way. Since we don’t always forget, or worse—hardly ever forget—it’s very easy for people to get complacent about doing something else to aid their memory, especially if whatever they need to do takes a bit of effort or if it seems silly (like putting a post-it note on the dashboard saying “Daughter in car seat” if you don’t normally take the child to daycare).

Another problem complacency causes is with recognizing change. We can all talk and drive at the same time. And we all know it can be a distraction. Sometimes it’s not too distracting (not too dangerous) and sometimes the conversation can be very pre-occupying (very dangerous). In situations like these, it’s easy to become complacent and rationalize what we’re doing when it’s not dangerous, because the risk is low. It only becomes a problem if the conversation starts to get more involved. But this can be difficult to recognize because you’re now thinking about whatever it is that’s pre-occupying your attention, not on what you’re doing (driving). So, even though we all know that driving when you’re really pre-occupied is dangerous, complacency can lead us to do things that may easily become very dangerous without us always recognizing it.

Another fairly obvious problem complacency causes is with overconfidence. Many safety devices, procedures or protocols are redundant if nobody makes a mistake or “nothing goes wrong”. We all know that you don’t need a life jacket unless you fall in the water. But if someone is a good swimmer, they might be less inclined to wear a life jacket; or if they were an experienced iron worker, less inclined to wear a fall arrest harness— especially if they were only 6-10 feet above ground…

‘right now’ is your last clear chance to do something to aid your memory.

However, people can also get complacent about using checklists and permits. They can also become complacent about things like telling someone where they’re going (hike in the woods) and when they’re planning on coming back—sort of like filing a flight plan. People can even get complacent about holding the handrail, even though we’ve all fallen going down stairs before and some of us have even fallen going up stairs.

So, as mentioned before, we need to teach people more than just the critical error reduction techniques they need to learn to fight complacency and to compensate for complacency leading to mind not on task; we also have to teach them to develop a deep respect for complacency and what it can also do to our decision making.

As it turns out, the man killed on the mountain bike was not an Australian—looking the wrong way—as was originally speculated. He was a ski instructor who had been living in the area for 30 years. Over 300 people came to his wake…

Every day, thousands (and thousands) of times a day, complacency claims another victim.

Larry Wilson has been a behavior-based safety consultant for over 25 years. He has worked with over 2,500 companies in Canada, the United States, Mexico, South America, the Pacific Rim and Europe. He is also the author of SafeStart, an advanced safety awareness program currently being used by over 2,000,000 people in 50 countries worldwide.

Get the PDF version

You can download a printable PDF of the article using the button below.