This article by Ray Prest was orginally published in the

Fall/Winter 2018 issue of the Safety Decisions Magazine

There’s never any shortage of debate in the safety industry. Just take a look at recent discussions at the American Society of Safety Professionals (ASSP) conference about the relative merits of behavior-based safety (BBS) and human and organizational performance (HOP).

In many ways, this debate is the crossroads of new and old thinking, with both sides attempting to provide answers to a complicated problem: How do we make workplaces safer for people?

Sometimes old things are new again with a slightly different perspective, and sometimes new things are heavily rooted in the past. In recent years, HOP is being discussed as a new philosophy for managing human factors in safety through a team-based approach to examining and designing safer systems and working environments. While the term is newly popularized, many of the concepts have been around for decades.

In a nutshell, a HOP-based approach creates and supports frontline learning teams—one of the five disciplines outlined by Peter Senge in 1990. It also prioritizes looking at deviations from systems and processes and then making adjustments to these systems. The goal is to make production processes more friendly for people and to build room in the work environment for human error.

BBS has been around for a long time. Every few years, a magazine headline asks whether BBS is dead, and the answer is always … well, debatable. The reality is that BBS is an effective and active process that many companies still use to drive safety engagement and improvements, though its overall use is in constant flux.

In a nutshell, a HOP-based approach creates and supports frontline learning teams—one of the five disciplines outlined by Peter Senge in 1990

The BBS strategy is to rely on others to provide feedback and guidance on personal behavior in their area of work. Various BBS programs espouse peer-to-peer communication and one-on-one observations and feedback systems. These are all designed around the notion that another set of eyes can offer useful insight.

BBS won’t die for good reason—its basic philosophy has been proven to work for over a century. For example, in the 1900s, Frank Gilbreth developed an observation and feedback system to watch bricklayers perform their job so that he could improve the efficacy and safety of his workers. He documented his findings in Motion Studies, a book published in 1911.

What’s been lost in the debate between HOP and BBS is that the two approaches aren’t mutually exclusive. Finding a way to deploy them in unison will help us get better, solve problems, and make improvements that will prevent injuries and save lives.

In fact, there are several ways that HOP and BBS can strengthen each other—and a few notable gaps exist even when the two are used in tandem. HOP and BBS focus heavily on making improvements to the work environment to account for human factors and prevent negative consequences when errors naturally occur. But human factors are best managed by humans, and each person needs to think about risk in real time and make adjustments accordingly.

The biggest gaps with BBS and HOP are the frequency of improvement opportunities and the fixed areas of focus. HOP teams will eventually cover most areas of the workplace, a chance to speak with most workers about their work area. But there are huge gaps between these interactions. A lot of things can change for employees over the course of a shift. And what about when they leave the facility and drive home, where they won’t have teams and peer observers to help them?

This is why BBS and HOP need to include personal safety skills training as the third leg of the stool. Each person needs to be able to think about human factors, errors, and systems solutions within the context of the work or task he or she is doing at any particular moment.

Worker safety depends heavily on a personal understanding of risk. People need the knowledge, skills, and habits to understand and think about how human factors like rushing, frustration, fatigue, and complacency increase risk, breed injury-causing errors, and cloud decision-making. This is especially true if you want to capture and leverage near-miss and Safety-II scenarios to identify variability within normal work where everything is going right. And doubly so if you want to prevent errors before they happen rather than manage them as they occur.

Common Denominators and Best Practices for Safety Improvement Strategies

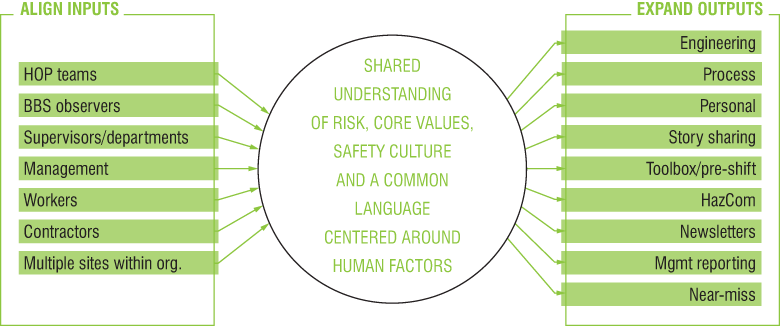

To be a truly safety-conscious company, HOP, BBS, and human factors awareness need to intersect. If frontline workers have an understanding of human factors, they will be able to offer not only more but also more meaningful input to the HOP team or observer. And with more and better input from frontline workers, those with specialized knowledge about engineering solutions can make additional and more accurate improvements.

To be a truly safety-conscious company, HOP, BBS, and human factors awareness need to intersect. If frontline workers have an understanding of human factors, they will be able to offer not only more but also more meaningful input to the HOP team or observer. And with more and better input from frontline workers, those with specialized knowledge about engineering solutions can make additional and more accurate improvements.

Ideally, individuals, observers, and teams will have a shared understanding of risk and a framework for consistent thinking and communications so that everyone can understand and apply them in their work areas and personal lives.

HOP-style teams will likely come up with more robust solutions to problems within their shared pool of knowledge. BBS will help get quality outputs from the observations by recording, tracking, and reporting the improvement suggestions to management. And nothing can compare to the number of inputs available to individual workers throughout the day.

It’s like combining two different approaches that parents take to protect their kids—safety in numbers and self-defense classes. Groups help with safety, but individuals also need to be able to look out for themselves.

You also need a strong safety-focused culture that supports all three of these activities and an effective, nonpunitive communication platform to ensure best practices and improvement strategies are disseminated to all staff, work groups, and sites within your organization.

Measuring the success of any improvement strategy is also critically important. Engaging the entire workforce in human factors improvement up front will also boost the quantity and quality of leading indicators as you move forward.

Supervisors need to understand human factors so they can temper the flow of work when they observe human-related risk and also predict risk before it occurs. Furthermore, you need senior management to commit time and money for training and to allow room for regular conversations and reflections. Company leaders also must set expectations for everyone, monitor accountability, and ensure that the physical improvement suggestions are implemented.

Develop an Efficient and Effective System by Aligning and Maximizing Safety Improvement Strategies.

If you have an improvement mindset going into any debate, you’ll have more opportunities—you’ll see discussion points as items you can add or subtract from your current state without having to sacrificially choose this over that, zigzag from one thing to the next, or get caught up in who’s right or wrong.

Engaging the entire workforce in human factors improvement up front will also boost the quantity and quality of leading indicators as you move forward

The key is to recognize that safety philosophies like HOP and BBS aren’t an either/or proposition. There’s no need to get caught up in which one is the best option, because they play different, but complementary, roles.

When combined with human factors training, the trio can actively reduce the risky environments, behaviors, and states that put workers in danger. If all three are implemented properly, organizations will be better and safer by leaps and bounds.

Ray Prest is the Director of Marketing at SafeStart, a safety company focused on human factors solutions that reduce preventable death and injuries on and off the job. A columnist for Safety Decisions since 2015, Ray’s been helping people learn about safety and training for over 20 years. Read more at safestart.com/ray.

Get the PDF version

You can download a printable PDF of the article using the button below.